We asked climate scientists gathered for the annual Comer Climate Conference to tell us about a place that will be dramatically altered by a changing climate. Their poignant responses underline a common theme; there isn’t a place on earth that will be left untouched or a person that won’t be affected in one way or another.

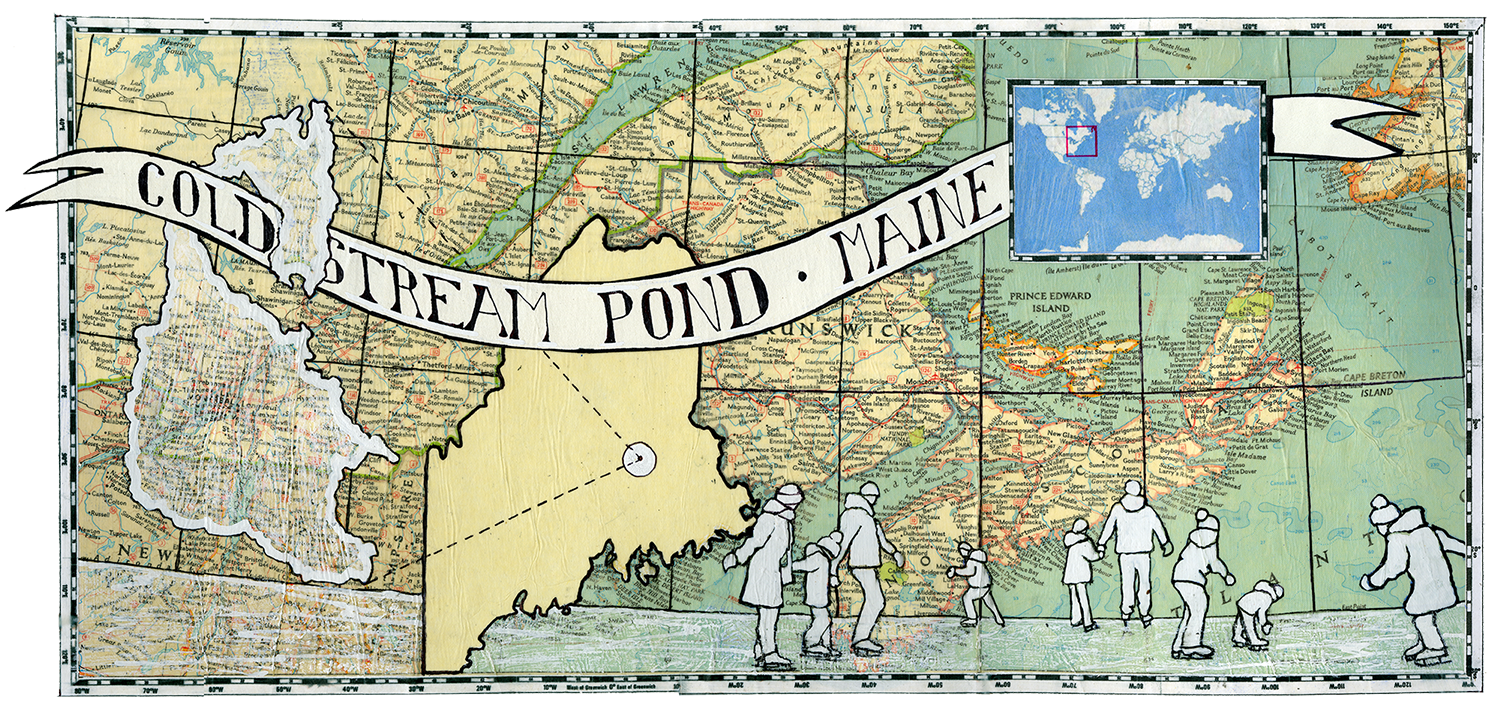

Cold Stream Pond

I grew up in central Maine, living on a lake called Cold Stream Pond. And that lake, of course, freezes every winter, given the Maine winters, but the number of days that the ice is there has been decreasing over the years. I’m going to be very sad when Cold Stream Pond can’t be walked on in the middle of the wintertime.

TOM LOWELL

Professor, Department of Geology

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI

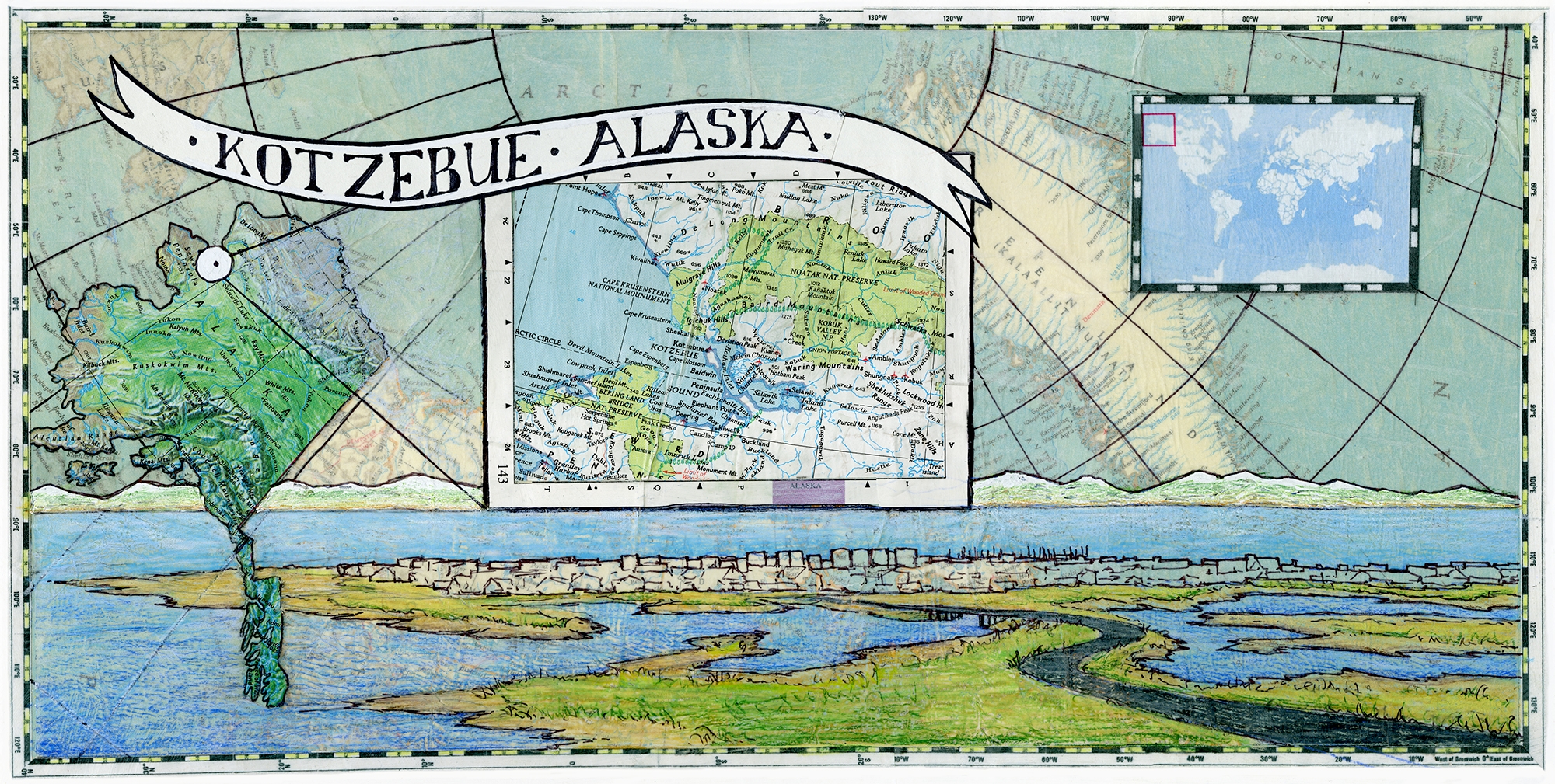

Kotzebue, Alaska

I grew up in Kotzebue, Alaska, which is an Eskimo fishing village 31 miles above the Arctic Circle, on the Chukchi Sea, which is actually part of the Arctic Ocean. I’m afraid to go back, actually, because I’m afraid that the place that I grew up in, that I loved, that was beautiful, that was the best place to grow up, will never be the same, because it’s on this sand spit which is actually at the foot of the Kobuk and Noatak river systems, and it drains the Brooks Range. I grew up on dog sleds, and hunting, and it was beautiful. And it’s changing, changing dramatically. It’s open now. The Northwest Passage is open. We could only get a barge in every once in a while, once a year, and now it’s just open. Now they can do it almost all the time. Breakup we’ve already seen it. Kotzebue will never be the same.

Joellen Russell

Thomas R. Brown Distinguished Chair of Integrative Science Associate Professor of Geosciences and Planetary Science

THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA

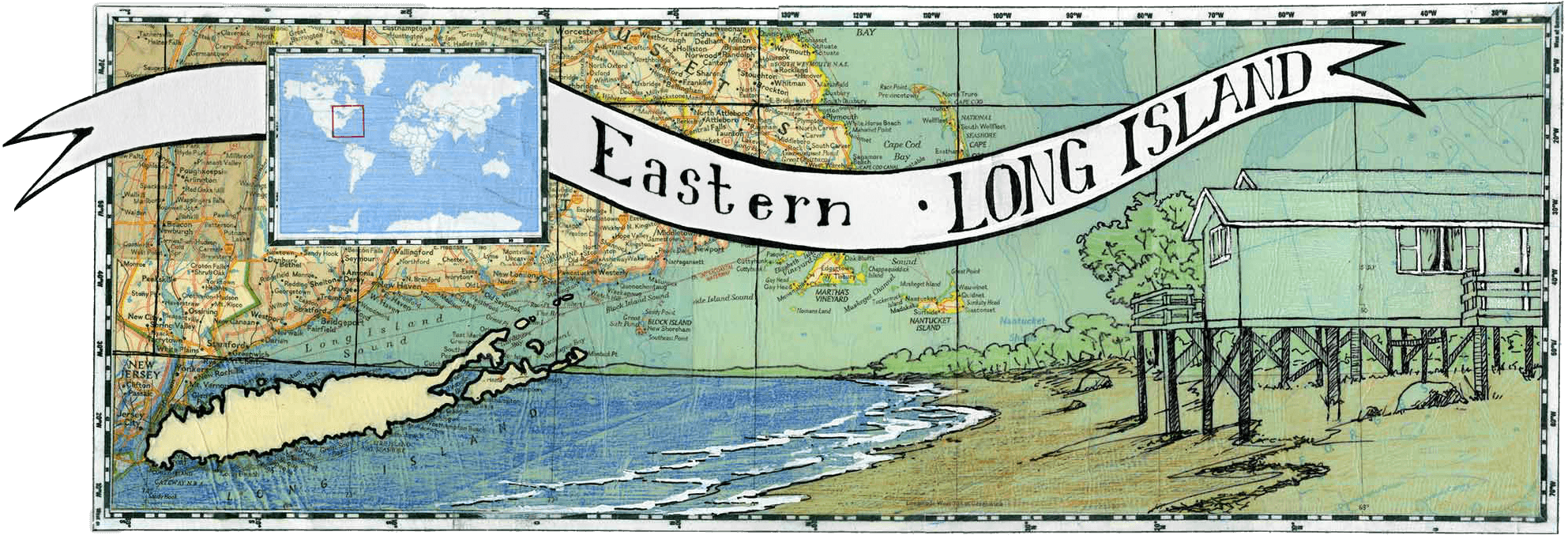

Eastern Long Island

In the 1950s, my grandfather built a house in a really beautiful spot on eastern Long Island a couple meters above sea level. I have spent some part of every summer of my life there, so the last 53 years. And over that time, I’ve watched the distance between the back porch and the beach get smaller and smaller. The place is unfortunately in a location where the earth’s crust is going down and the global sea level is going up. And it won’t be too much longer before we won’t be able to use this place anymore. And it’s an interesting dilemma for a scientist to try to figure out how to handle where we love the spot and would love to just keep going there with our families and our kids, but probably won’t be able to.

Ed Brook

Professor, Geology Program Director

OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY

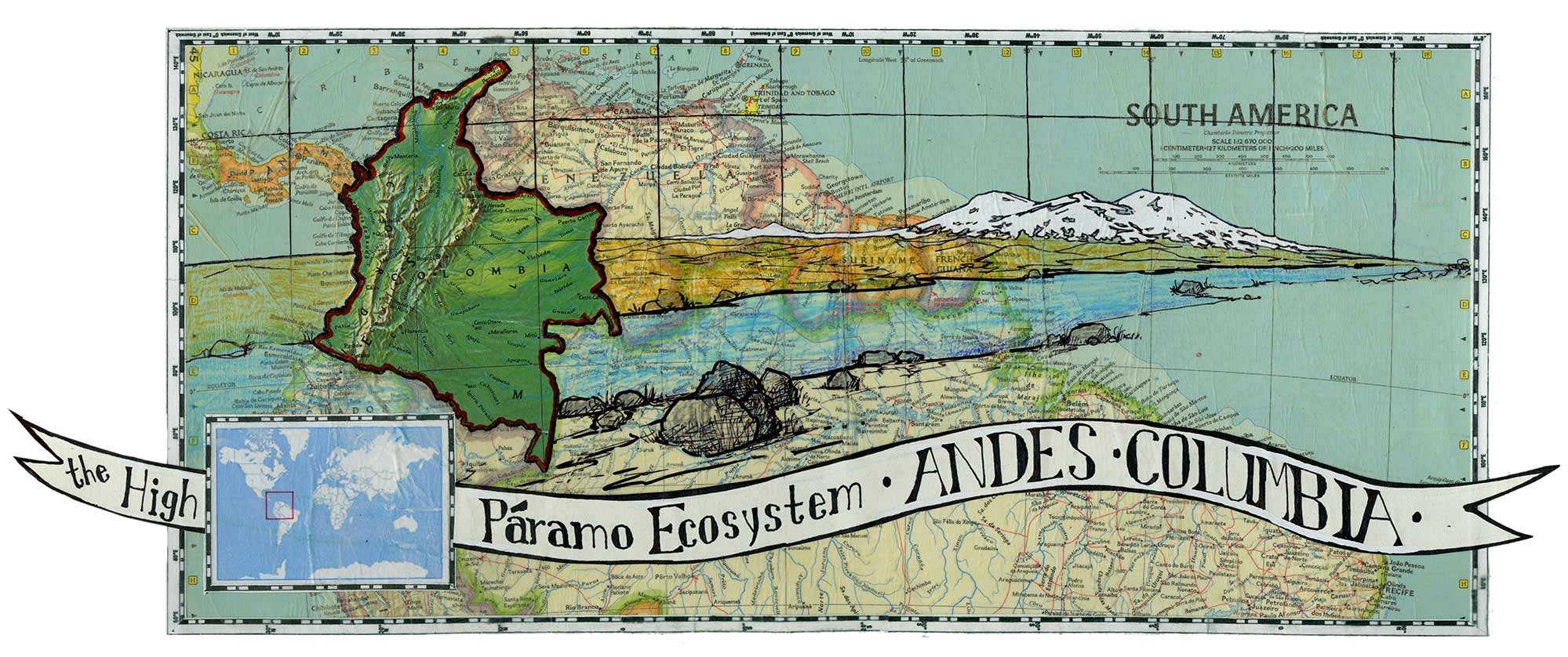

Glaciers in the Tropical Andes

Somewhere I work that I know is changing now, quickly, is in the tropical Andes. And this is in Colombia specifically. The glaciers there are beautiful, but they’re shrinking so fast that they should be gone in about five or ten years. And that’s incredibly fast for any kind of change, and it’s important there because it’s not only a water resource, but it’s also, it’s part of the high páramo ecosystem. As the climate has warmed up, the clouds have disappeared during the dry season, so they’re no longer shielded from the sun. This is happening now. It’s the fastest warming place on earth.

Gordon Bromley

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND GALWAY

School of Geography & Archaeology

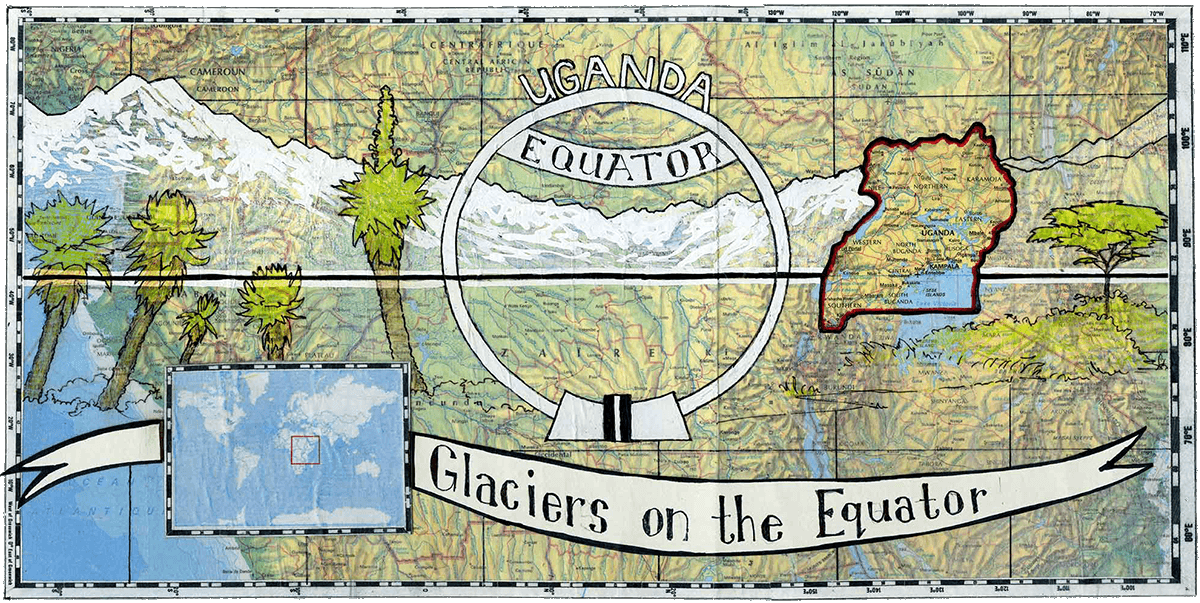

Rwenzori, Uganda

One place where I think that climate change is really going to affect people is in the high mountain regions of the Rwenzori in Uganda. I talked with a park ranger who studies tourism for the Ugandan Wildlife Authority. She said 'It is difficult for people to believe there is snow at the equator. People need to see it for themselves. It will not have the same effect when the snow is gone, when the glaciers are gone.' The tourism to the Rwenzori is largely to see these glaciers at the equator and see the snow, and so it’s really difficult to explain to her that with one degree of warming, these glaciers are essentially gone.

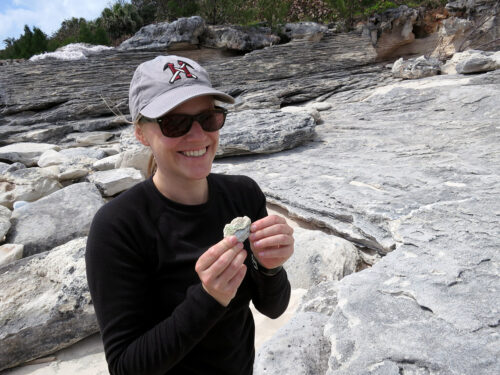

Alice Doughty

DARTMOUTH UNIVERSITY

Neukom Fellow Department of Earth Sciences

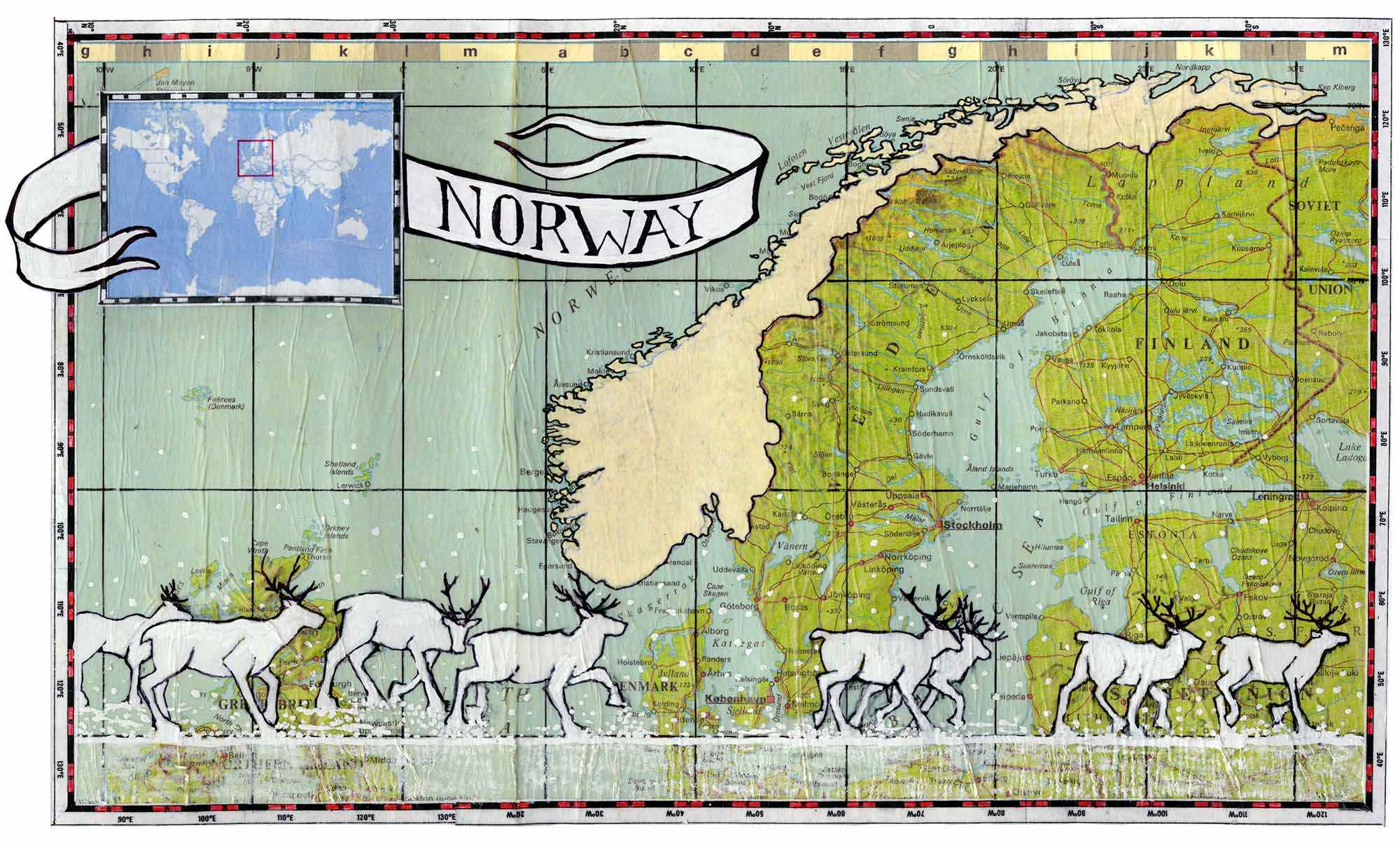

Norway

I spent two months living with Sami reindeer herders in Kautokeino, Norway, which is at about 70 degrees north. And the reindeer herd is only semi-domesticated, so they partake in this migration from the tundra to the coast every summer, and the timing of this migration is up to the reindeer. And because the winters have been so shortened, the snow is much softer now when they’re trying to get to the coast, which makes them kind of trip over their own hooves. Some of them don’t make it anymore. So not only is this bad for the reindeer as the winters shorten, but also for the herders, whose livelihood depends on these animals.

Alexandria Balter

THE UNIVERSITY OF MAINE

Research Assistant School of Earth & Climate Sciences

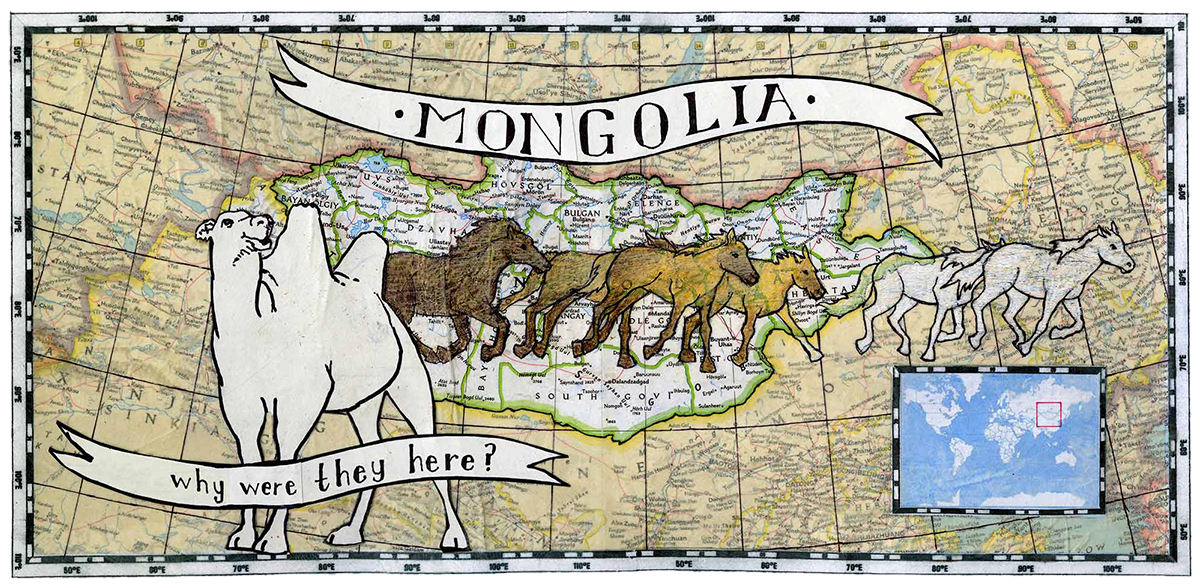

Eastern Mongolia

I was using a soviet map made in the 40’s to get around. When you look at the map, you see all of these lakes spread out across the region, so in my imagination, I saw the Finger Lakes. I also knew that a paper published a couple of years ago claimed that lakes in Northeastern China and Eastern Mongolia have been drying out at an alarming rate, and that over the past 30 years about 30% of lakes have evaporated. When I got there and started driving around I was shocked to see that in many of these lakes, instead of water, the only thing glittering in the sun was a thin layer of salt left over after these lakes completely disappeared. Lake Khukh is the biggest lake in the region and the lowest point in Mongolia. One afternoon, we started driving along this dirt road to get to another point North of where we were. We didn’t reach the lake, it disappeared from that part and we could just drive on the dried lake beds. What made this experience even more disturbing was that in the center of the dried area, were three Mongolian camels standing there, eating. Now just to clarify, this is the heart of where Genghis Khan roamed, the iconic land of the horses. Camels live in the Gobi Desert some 500-1000 km south of where we were. Why were they here?

After talking with the locals, I found out that ground water has been decreasing, forcing them to move to other places or dig wells 4 times deeper than before. The camels seem to be part of this transition, the water is becoming scarce and camels are better adapted to these conditions. So the homeland of the famous Mongol horses is drying out forcing the horses and their nomad horseman to change. Mongolia is smack in the middle of an area that is warming about twice as fast as the global average. What are the implications of this? If what we are seeing is a real trend, this will have dire consequences for northern China and eastern Mongolia and will affect a great number of people.

Yonaton Goldsmith

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

Graduate Student, Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory

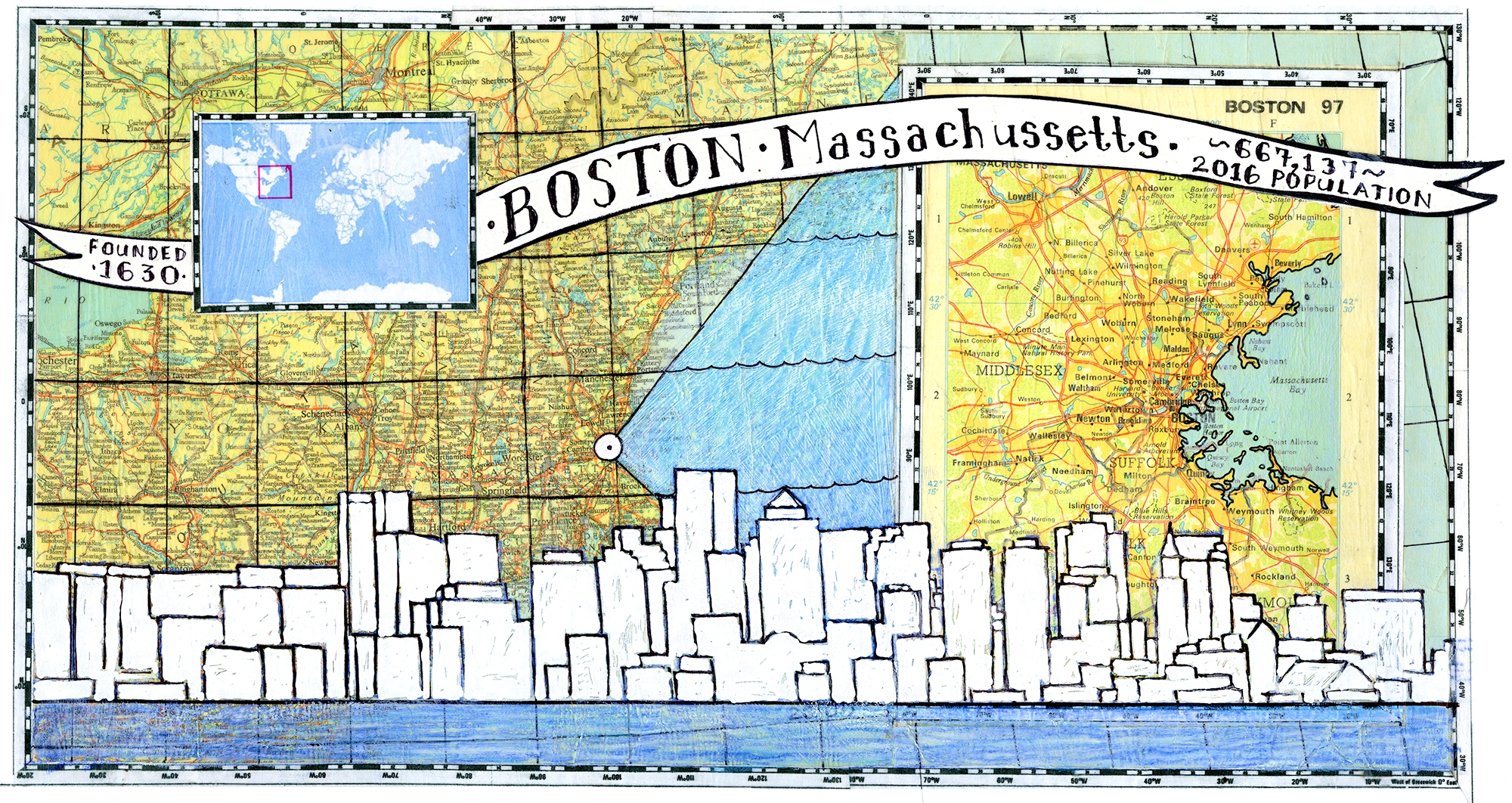

Boston, Massachussetts

Boston is a place that will be impacted by climate change and to illustrate that I brought a map of the city’s extent from 1885. Boston will be affected by climate change because of sea level rise. What is less known about that is that Boston as well as most of the U.S. East Coast will get hit double by sea level rise because in addition to the seas rising, the land is going down. The reason for this lies way back in the past, 20,000 years in the past in fact. During that time, which was the height of the last ice age, big ice sheets covered most of Canada pushing the land down, which resulted in areas around it, i.e. the U.S., to go up like a lever. Now that that ice is gone, Canada is popping back up and big swaths of the US are coming back down. In some places this subsidence is as large as the water rising due to polar ice melt with the result that sea level rises there twice as fast as most other places. Boston is very close to my heart because I lived there for 5 years and I remember walking through the seaport district, visiting the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Art) or Harpoon Brewery or taking off from Logan airport. But looking at this map from 1885 none of this is there, it’s all just water. What happened is that through landfill the city expanded and they built more and more into the ocean filling up the bay. All these areas are right at sea level and will therefore be very susceptible to storms and sea level rise, which will result in flooding of streets, building and tunnels.

Jacqueline Austermann

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

Newton International Fellow Department of Earth Sciences