Tucked into the shelf of early 20th-century high rises that line Chicago’s historic Michigan Avenue is a world-class museum.

The Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago (MoCP), founded in 1976, offers bold, thought-provoking exhibitions and dynamic programming drawing from a vast collection of over 17,000 works. Museum Director Natasha Egan joined Comer Family Foundation Creative Director Alison McKinzie to discuss photography, MoCP’s latest exhibition, and the museum’s plans for a reimagined home.

The following is a condensed version of our May 2024 interview.

AM: Many of our readers will be familiar with MoCP, but for those who aren't, let’s start with a little background. You're in the heart of a bustling city. You're a member of the American Alliance of Museums and part of Columbia College Chicago. You curate pioneering contemporary exhibitions throughout the year and host free programs inspired by your exceptional collection. On a recent visit, I found the museum teeming with students and their professors engaged in lively conversation. I am wondering as the director of the Museum of Contemporary Photography, what do you see that makes it so unique?

“Photography touches on everything. We live in an image-saturated world and we learn how to navigate the world through images.”—Natasha Egan

NE: What I love about MoCP is that while there are a few institutions specifically focused on photography, we are a medium-specific as well as an academic art museum. Photography touches on everything. We live in an image-saturated world and we learn how to navigate the world through images. This isn't new of course, but it's heightened now. The role of the image has always been prevalent in how societies are shaped. To have a museum working with artists using photography to tell stories, whether deeply conceptual or documentary, offers the ability to see the world through an artistic lens. Photography has many different levels of purpose – it's used to document; it's used to advertise; it's used to take pictures of nature and record family life; and it’s used to make art. It captures our humanity and creativity while covering every topic that’s currently being grappled with. MoCP's mission is to explore the role of image in society and what we learn from that – whether it's art, whether it's science, whether it's about climate change, whether it's war, whether it's colonialism or immigration.

Many academic art museums start by having an alum donate their collection, which can be one particular viewpoint. We started very differently. The head of the photography department in the 1970s and a group of Chicago collectors wanted to carve out a place for the role of photography in the fine art sphere. Photography had always been a little on the outs with contemporary art — critics thought it doesn't have the artistic hand, it's mechanical, photographers doesn't have to work as hard as artists, photographs can be reproduced, they’re not of one-of-a-kind — there were so many questions that came out of photography trying to find its place as a fine art and in academia. In the 70s, the museum began showing this thriving field as it worked to gain acceptance in the art world. This was augmented by our collection strategy. We've been collecting from our exhibitions since 1979 and receiving donations and today we have over 17,000 works in our permanent collection.

Everyone is a photographer. Is everyone an artist?

AM: This moment seems a similar point of crux for photography’s role. Today, photography is more and more accessible from a technological perspective. Many people have a camera in hand at every moment and use it for many different purposes. While most haven’t been trained in photographic techniques or in commanding an artistic eye, photography becomes an extension of seeing.

N.E. When I first came to the museum, we would have battles around how to refer to “artists” and “photographers”. Some photographers were adamant, “I'm not an artist, I'm a photographer – why not keep me where I belong?” And many artists were like, “Don't you dare call me a photographer, I'm an artist.”

We would invite an artist to exhibit at MoCP and while their work was 100% photography, they didn't consider themselves photographers. They were just using the medium of photography to create their art. Early on, some people would say “No, I don't want to exhibit at MoCP, because I don't want to be pigeonholed into the photography world, I'm an artist.” Fortunately, that idea has evolved, and now people are excited to exhibit with us whether they consider themselves to be photographers or artists. I heard it enough in the 90s to think “Wow, this is a medium where people want to be careful not to fall into being a ‘shutterbug’”.

Natasha Egan, an accomplished curator, has served as MoCP's Executive Director since 2011. Portrait © Brooke Hummer Photography.

“As photography became more accessible, it became a medium of democracy.”—Natasha Egan

The history of photography is a bit exclusive. Photography was technical and expensive — the cameras, the chemicals, the glass plate negatives. Even when Kodak introduced packaged film, it was still expensive. It was a privilege to have access to a camera. As photography became more accessible, it became a medium of democracy. With that, you get more of the dangers that democracy encounters around freedom and ethics. People assume a photograph is true because it's recording something that exists. But, you can take a picture of something, and in your opinion, you're taking a picture of a particular scene. But in another person's opinion, you're taking a picture of something different. You're taking a picture of a person standing on the street. You can't know anything about that person standing on the street without knowledge of that person, and why they're standing on the street, and that's where everything changes, and that's where the tone of the picture can change. You might print a picture darker to convey a mood, and I'm going to print mine lighter to convey a mood, and all of a sudden that picture represents something very, very different. And in art photography, you can do whatever you want. It's not necessarily just a record or document. That's when it gets super messy.

What is photography now?

AM: Photography has had so many inflection points along the way. We lose sight of these debates because now everyone is a photographer. We could celebrate that more because it informs and changes how we see, how we communicate, and interact with the world. But at the same time, if everyone's a photographer, that accessibility adds complexity.

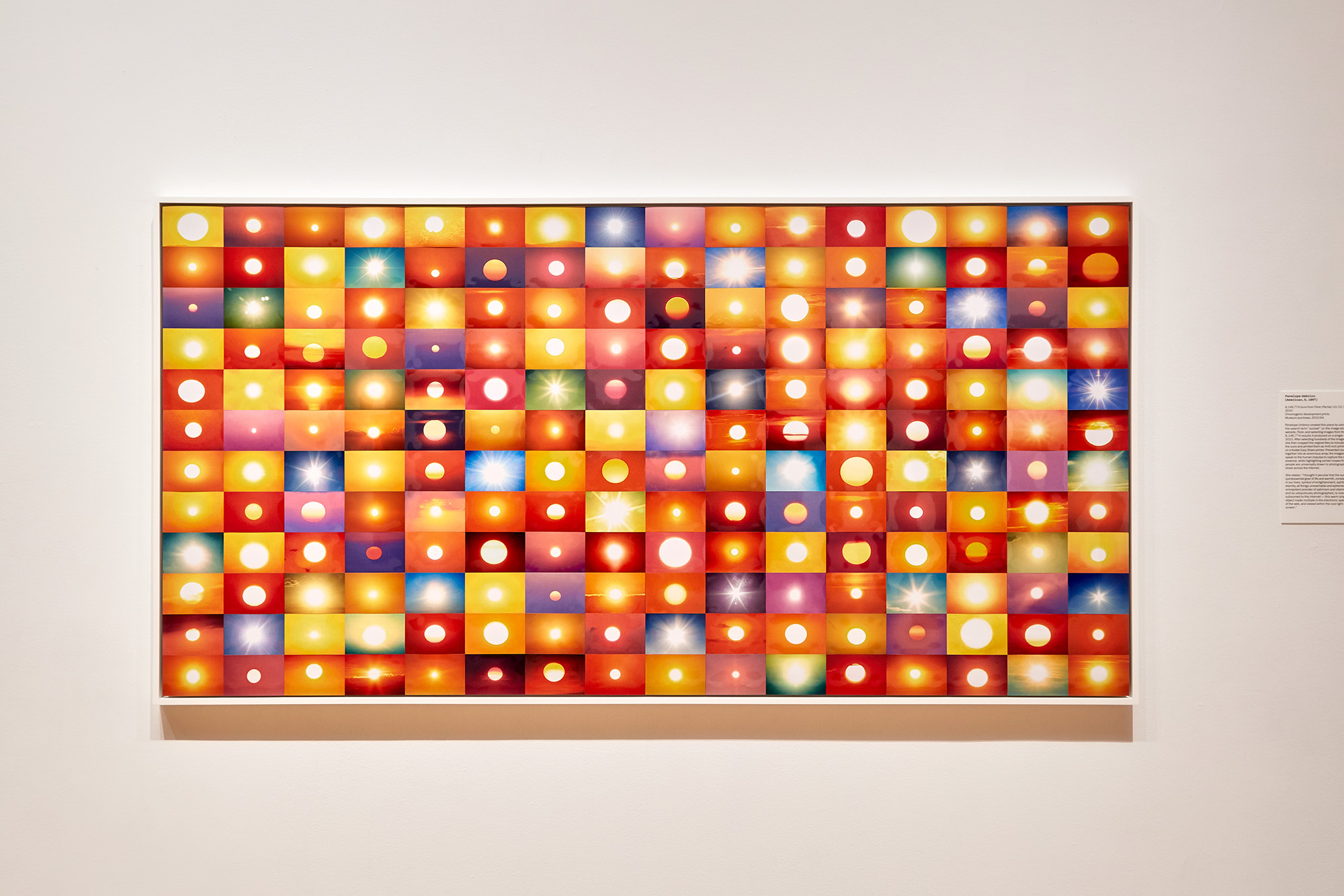

NE: I love the mix of “everybody is a photographer” and that we are a museum showing artists working with that idea. There's a wonderful artist named Penelope UmBrico who focuses on images circulating on the web. One piece is in our summer show, Captured Earth, curated by Kristin Taylor and looking at ways artists grapple with creating visual language to express their connection to the earth and its magnitude. Umbreco’s 7,626,056 Suns From Flickr (Partial) 9/10/10, (2010), presents an assemblage of photographs of the sun from one day found on Flicker on September 10, 2010 to underscore the universal human attraction to capture the sun’s essence. It's a large piece (8-by-4-feet) with individual small color pictures. In 2010, 8 million images of the sun were uploaded on a given day. Do you know how many people probably uploaded a picture of the sun yesterday? Probably in the billions. That is their picture of the sun. They take ownership of that picture. People might take issue with Penelope using their picture in her art, even though she crops each one so that you don't have the surrounding landscape. It's just the ball of the sun. But these millions of suns were uploaded on that day.

So that's an artist who is talking about the importance of capturing the sun, of why as humans we love to photograph the sun, or the sunset, or the sunrise, or the eclipse. We wouldn't be here without that sun.

7,626,056 Suns From Flickr (Partial) 9/10/10, (2010) by Penelope UmBrico is featured in Captured Earth, MoCP's summer exhibition. The show explores artists grappling with creating visual language to express their connection to the earth and its magnitude.

NE: But then it gets interesting when people say, “but, that's my picture.” They all look similar. Of course, you can have ownership of your picture of the sun. People may have ethical issues when an artist repurposes an image. Still, if they’ve uploaded an image for the public, it's the same as getting upset if they see themselves in street photography — the street is free space. You could argue if someone uses another person’s image as an advertisement and makes money, that's not allowed. Defining and regulating artistic freedom is much more challenging.

In MoCP’s exhibitions, we often focused on themes looking at what is happening at the moment, but as soon as we decide to acquire contemporary work for the collection, it becomes historical. Our mission is to constantly be on top of what's happening with photography today. Today the hot topic is artificial intelligence and authorship. Not long ago it was about the digital revolution. And before that the question was is color photography fine art or commercial? In some people’s view historically, fine art photography had to be black and white. It took a long time for color to be accepted, and the same thing happened for digital. It has always been the commercial and technical side of photography that fed the artistic side – from advertising to the U.S. Geological Survey. You’ve got to make better cameras so that the surveyors can better survey our country. There's always a technical need. And, it is not super appropriate but completely relevant that pornography is always the first to embrace the next technology.

AM: Going back to navigating our image-saturated world, how do you see MoCP’s singular collection strategy serving as a resource?

NE: We often collect work out of the exhibitions we are organizing. Many of our shows focused on emerging artists in thematic group exhibitions where each artist may be grappling with a similar theme in very different ways. Sometimes we are giving artists their first museum show. We’ve never played the art market game. Our collection may have a lot of holes. If we never showed an artist we may have missed them because we didn't have the financial means to purchase work when it reached a certain level in the market. Our collection is like no other because it's been formed from our exhibition history and serves students as a learning tool. But because we have received some amazing donations of photographs, we have a wonderful historic collection as well.

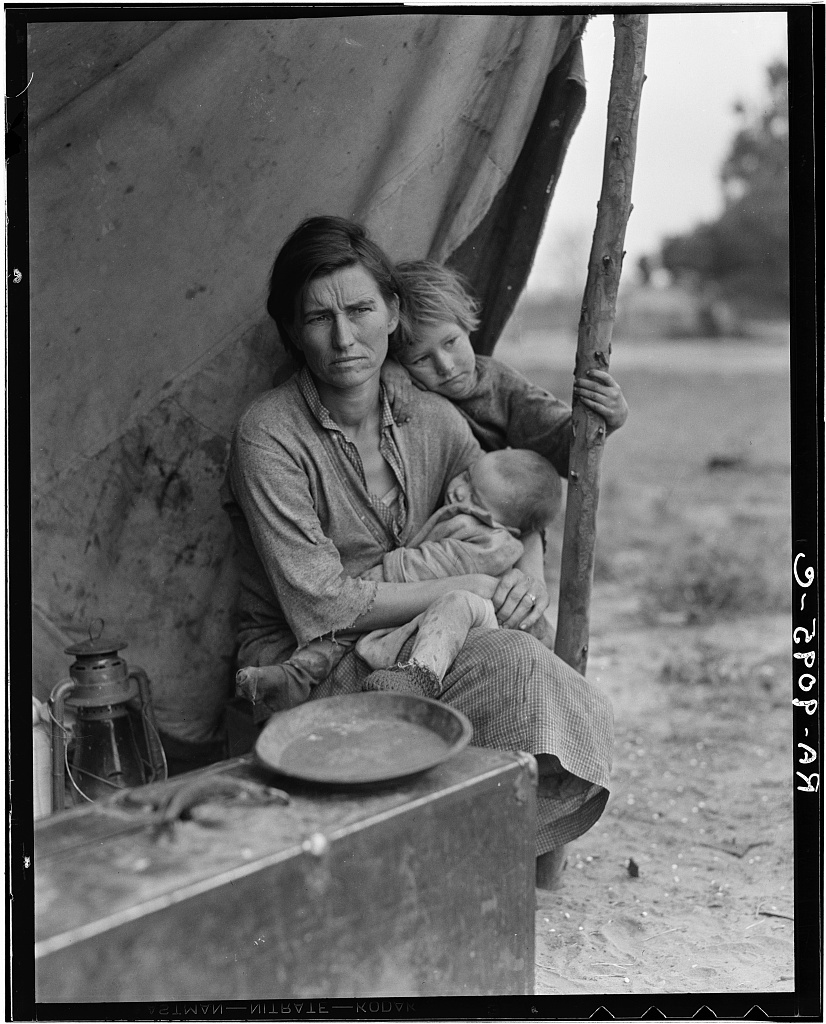

Migrant agricultural worker Florence Thompson with several of her children in a tent shelter, Nipomo, California, Dorothea Lange, 1936, LC-USF34- 009098, Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

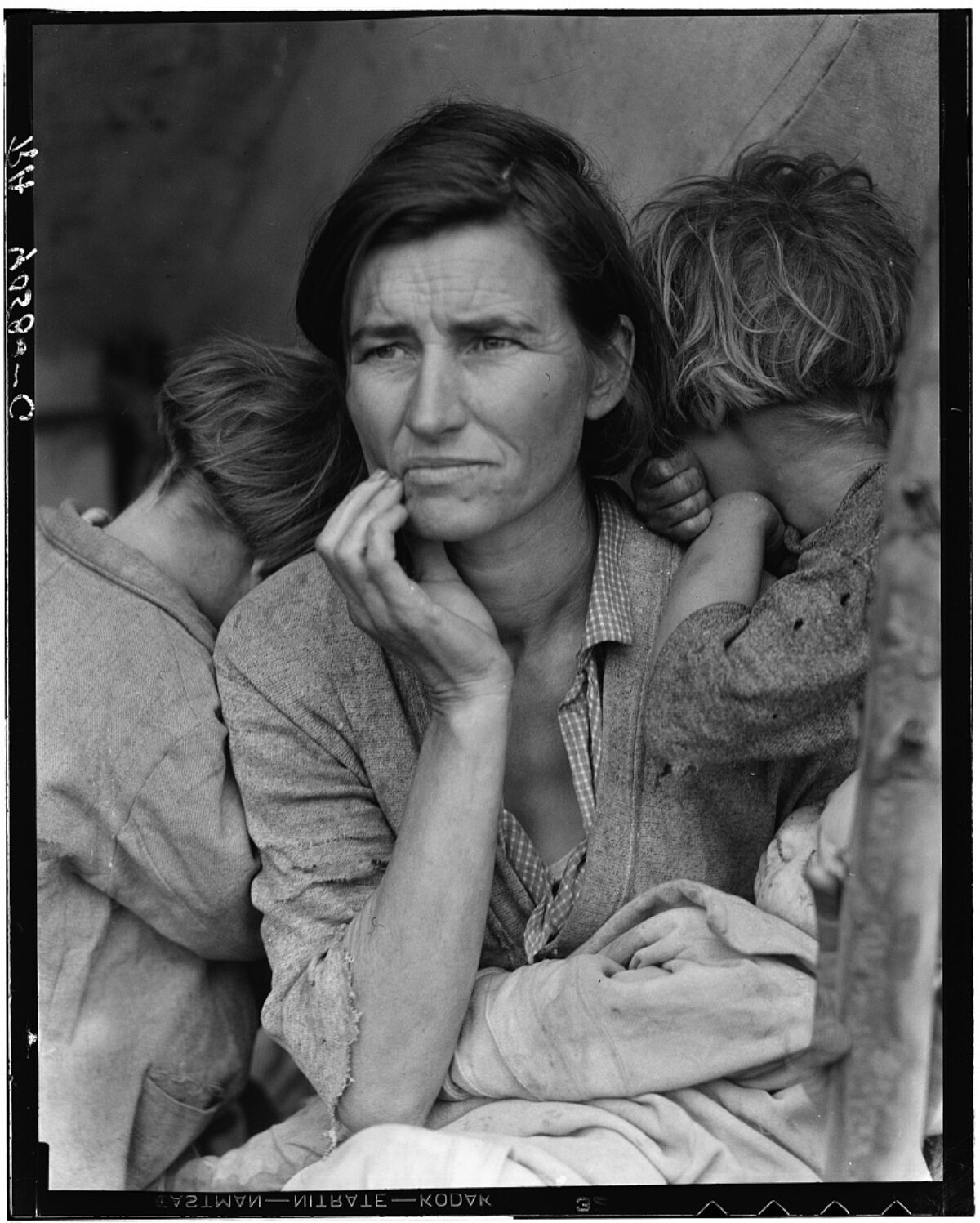

Florence Thompson, aged thirty-two, mother of seven children. Nipomo, California, Dorothea Lange, 1936, LC-USF34- 009095-C, Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

One of our greatest holdings is about 500 of Dorothea Lange's work prints from the 30s, 40s, and 50s. It's a real treasure in Chicago. Her work from the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA) is held between the Library of Congress and the Oakland Museum. But we're the only place in the midwest with this little pocket of her work and it is often shown, studied and borrowed. It’s remarkable for a teaching institution to have these works. You can see her process behind the famous picture of a migrant mother shown on the cover of Life magazine in 1936. But we have all of the different versions. You can see that she took a picture from far away. There were 6 kids in the picture or seven kids in the picture. And then, as she got closer, some of the kids left and the last one shows the mother with just two children and it becomes representative of the Great Depression. Seeing the process changes how you think about this picture. She did not just come upon the scene, and ‘ohh and click’, and had this great picture. No, she's got an entire contact sheet of different versions. It wasn't one click of the shutter. It was a lot of moving in, moving closer, moving to the side, losing some of the kids. It changes how you think about photojournalism and how it differs from documentary photography where you study a subject over time. Photojournalism can be more about where the journalist happens to be standing to catch a fleeting moment. Journalism can also be documentary, researched, and planned to tell a story.

Understanding that it took Dorothea Lange multiple frames to get to that iconic image that tells the story of the Depression is such an important piece of the idea around everybody being a photographer now. Framing something a certain way tells a certain story. You see more people doing it intuitively, but maybe they're referencing the whole photography canon.

Migrant Mother, Destitute pea pickers, Nipomo, California, Dorothea Lange, 1936, LC-USF34- 009058-C, Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

The museum as a space for curious minds

We use our collection in so many unexpected ways. People may think only photography students learning about landscape look at landscape photos. And that's so far from what we do.—Natasha Egan

AM: People learn by looking at social media and what they find online – which has been informed by the history of image-making. Maybe they're not in art school, or looking at photography books, or going to exhibitions, but they see how someone frames a portrait, or a landscape, or a plate of food, or a street scene. It's wonderful that the museum is a home for the students to develop their unique photographic eye while delving into your collection.

NE: I always think of the collection as the heart and soul of MoCP because there's such a great range of works. Through our print study room, we serve photography classes as well as classes from all disciplines. We offer courses that address themes such as gender or the environment. We have brought in law students from the University of Chicago to discuss ethics around how photographs document and how that can be challenging. We have work that creates awareness and ensures that academia is having a dialogue.

We also teach classes to art therapy students. One of the most important things for any therapist or health provider is learning how to read people. And one way is to learn how to read images of people. What is their body language? Why are they hunched over? What can you learn? Because what somebody tells you is sometimes very different from what their body is telling you. Because we have so many pictures of people, we've done courses where art therapists use our collection to read human behavior. What are you seeing? What are you thinking? What are you feeling when you look at this picture of this person or this body, or this expression, or of this shadow. Shadows tell you a lot. We use our collection in so many unexpected ways. People may think only photography students learning about landscape look at landscape photos. And that's so far from what we do.

We pride ourselves on being accessible. We host many high schools and colleges from around the region. If you have a topic in mind, maybe you’re looking for work about body language, well, we have some ideas — it's a collaborative experience. We also have set print viewings on a range of topics: identity or environmental issues, immigration or the City of Chicago, or the fundamentals of photography. Teachers can select themes that resonate with their class. We're always pulling works out for anyone who would like to come to the print study room.

AM: That is a perfect segway into your renovation plans and how your new vision for MoCP will enhance accessibility.

MoCP's focus on the future

“Architecturally we are a hidden gem, but I don't want to be hidden any longer.“—Natasha Egan

NE: When you walk into Columbia College at 600 S. Michigan, you might not know we're there. Our 1907 space was originally designed as a showroom for International Harvester tractors. We still have giant steel beams where the tractor engines used to hang. Photography doesn't like light so the street-level windows are covered. We have the idea to reimagine our space to be more accessible and frankly better for viewing our exhibitions and collection. The current space is not conducive to the full experience that we're looking for. We want to reconnect to Michigan Avenue and Grant Park, welcoming the city rather than being secluded from it. We want people to see inside the museum from the street. We want to create spaces where you're encouraged to linger or even come and sit down and check your e-mail or whatever you want to do. Some of my favorite museums, the International Center for Art in Boston and the Whitney, have compelling spaces where you leave the gallery and you're suddenly looking out at Boston Harbor or the Hudson River. And then you go back in and take in the art. I love the idea that you always know where you are.

MoCP's Focus on the Future campaign reimagines the museum space for increased accessibility, versatility and visibility.

NE: Our new space will bring in more natural light while moving the darkened galleries to the interior. Currently, we don't have an elevator inside of our space. You can only access the 2nd floor by exiting the museum and taking Columbia College’s elevators. The mezzanine remains inaccessible. We will add an elevator to take both people and large artworks between the floors. We will have dedicated galleries and a separate print study room classroom. We want to expand the storage vaults to better care for our collection. As works have increased in scale, we’ve outgrown our 1997 cold vault, or as we call it, the meat locker.

Our print study room symbolizes what we do educationally. We're naming it the Dawoud Bey Education Center after the photographer, a long-term professor at Columbia College who is now retired.

In 1993, MoCP commissioned Dawoud Bey to do a project with the college and some Chicago high schools using a 20 by 24 Polaroid camera. Columbia students helped him with the residency — it was a wonderful collaboration. We produced his first exhibition in Chicago and one of his first large solo exhibitions. Five years later, Columbia invited him to become a tenured professor. The museum and Dawoud Bey have been very tight. He's curated shows for us and we've mounted several exhibitions with him.

This is all part of a project that we think is very important for the city of Chicago — a photography museum with its finger on the pulse of an ever-changing role photography plays that is open to all to explore, study, and enjoy.