Among glaciologist Richard Alley’s many gifts is his ability to tell relatable stories and analogies about the scientific questions he has studied for over 30 years. Take, for instance, his one about pancakes.

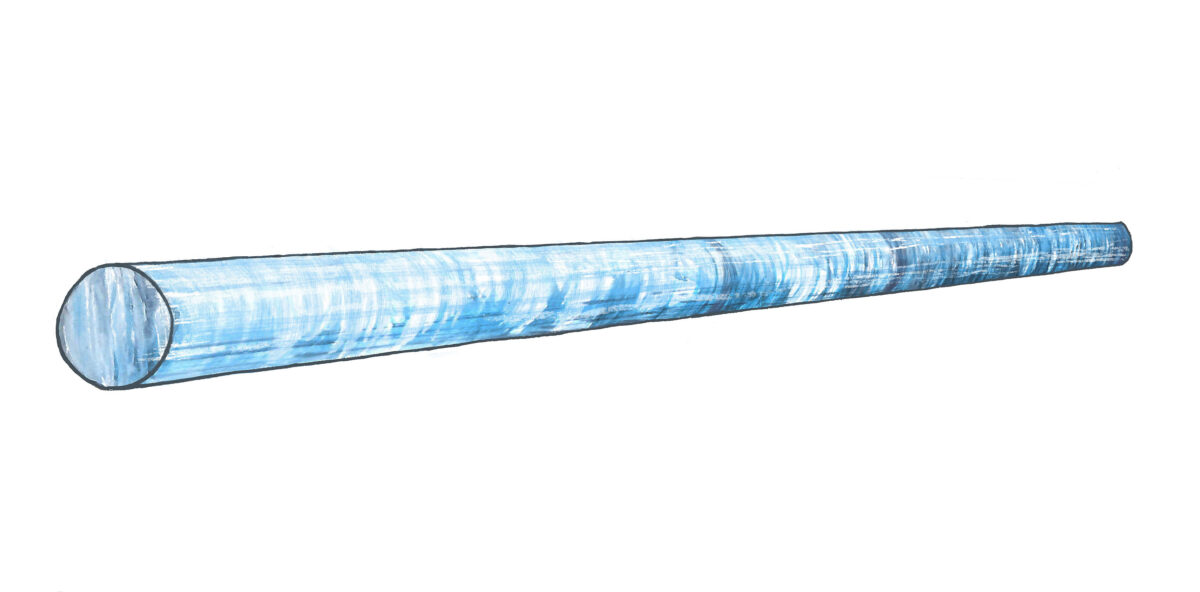

As a young researcher working on a project launched in 1989 by renowned climate scientist Wally Broecker, Alley helped extract ice core samples from Greenland’s glaciers. Alley affectionately called them "the ice folks."

What were the ice folks hoping to learn?

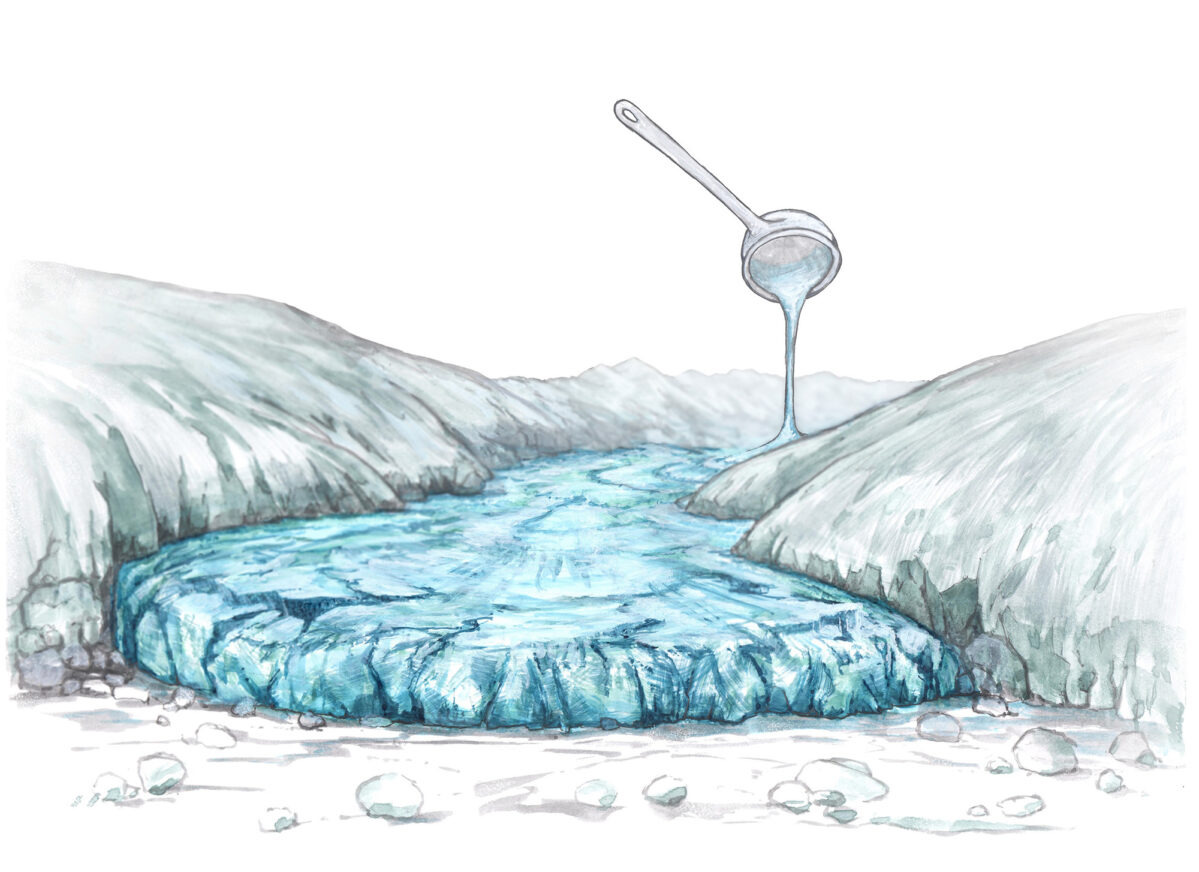

When you think about Greenland, Alley explains, “It's this giant pile of old snow squeezed to ice, spreading under its own weight.”

The east side goes east, and the west side goes west. “It's stretching and thinning like a pancake on a griddle,” he said.

The snow falls, then it spreads, and then “more pancake batter comes,” and it spreads some more. For the layers near the bottom, this spreading process has been occurring for more than 100,000 years, leaving very thin layers.

By drilling into the core of this “pancake,” the team intended to learn more about the history of the glacier and the climate, and especially to determine whether abrupt climate changes were real.

Alley uses analogies, like comparing the Greenland ice sheet to pancake batter spreading under its own weight, to help explain complex scientific concepts.

The Two-Mile Time Machine

Broecker showed “that sometimes there’s a fundamental reorganization of the ocean-atmosphere system that happens very suddenly,” Alley explained. But they didn’t know how suddenly.

Alley, who helped with the team’s site selection and glacial flow models, pursued further research and analysis. By studying windblown chemical indicators, such as sea salt, and methane levels trapped in the ice cores, he showed the connections within the glacial climate system. He helped answer the question about how suddenly the system changed. (Alley later described these cores as a “two-mile time machine” in his popular book of the same name.)

“We could count annual layers down to the transitions,” Alley said. “We could see that huge changes happened in a couple of years, and there were many of them.” The most famous one occurred at the end of the Younger Dryas, about 11,500 years ago with another at the end of the little Ice Age, about 8,200 years ago.

“We could count annual layers down to the transitions—huge changes happened in a couple of years, and there were many of them.”

—Richard Alley

Alley’s groundbreaking results, published in peer-reviewed scientific journals in the 1990s, helped sound the global alarm on the potential dangers of climate change. (Nature,1993; Geology,1997.)

His research suggested that because we’ve seen the climate shift rapidly under certain conditions in the past, it could shift rapidly again in the future.

“The excitement about the huge, widespread, abrupt climate changes was amazing, and led to really fast progress,” Alley said.

The National Academy of Sciences invited him to chair a panel of scientists exploring abrupt climate change. They framed the threat in the broader picture of scientific research and societal issues, and their work resulted in the influential report Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises.

Alley later joined the teams of climate scientists working on the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Their many reports estimating climate change's scope and impacts led to the IPCC's 2007 award of the Nobel Peace Prize.

He had come a long way from his graduate student days.

Alley's colleagues highlight that beyond his formidable scientific contributions, his down-to-earth nature and great communication also contribute to his impact. Alley has emerged as one of the most prominent scientists teaching about climate change threats, from massive open online courses known as MOOCs to the halls of Congress.

Now a professor of geosciences at Penn State University, Alley has written over 400 peer-reviewed scientific papers, which have been cited more than 50,000 times, a whopping number for any scholar.

He has earned so many prestigious awards for his continued work and leadership that simply listing them would require paragraphs. Beyond his contributions to the Nobel Peace Prize-winning IPCC team, two notable ones include the Heinz Award he won for a “vision and spirit that produce achievements of lasting good” and the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement.

“Richard's strengths are that he's brilliant, and he knows a lot about climate change, all aspects of it,” observes George Denton, a fellow climate science professor at the University of Maine and top scientist in the field. Denton and other scientists highlight that beyond Alley’s formidable scientific contributions, his down-to-earth nature and great communication also contribute to his impact.

“He’s incorporated into a lot of the climate studies because he knows so much,“ Denton said, “and he can bring such positive energy.”

“He's so highly regarded intellectually that we easily embrace him as a scientific leader,” said Jerry McManus, a leading paleoceanographer, Changelings member, and Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University.

“He connects easily to other people,” McManus said. “At the same time, he's a brilliant scientist. He's rigorous and quantitative and insightful.”

Alley downplays accolades like these. “My job description is to go to some of the most beautiful places in the world with some of the best people and learn what nobody knows and bring it back, share it with others, and make it useful,” Alley said. “We call that teaching, research, and service…I see these as intertwined.”

“Richard is such a brilliant communicator that he's essentially become one of the crucial voices of the scientific community for sharing information about climate change,” explains colleague Jerry McManus. “He can gain scientific insights and share them individually or very broadly.”

“I've spent a lot of my career listening to people tell me, well, shouldn't we wait on climate until we're sure? And the answer is no. Unequivocally not.”—Richard Alley

Uncertainty and wall phones: Sharing the science of climate change

Given his extensive knowledge and gift for storytelling, Alley quickly emerged as one of the most prominent scientists teaching about climate change threats, from 40,000-person massive open online courses known as MOOCs to the halls of Congress.

“Richard is such a brilliant communicator that he's essentially become one of the crucial voices of the scientific community for sharing information about climate change,” said McManus. “He can gain scientific insights and share them individually or very broadly.”

“I've spent a lot of my career listening to people tell me, well, shouldn't we wait on climate until we're sure?” Alley said. “And the answer is no. Unequivocally not.”

He argues the uncertainties of how much the sea will rise are too great. “Uncertainty is not your friend in this. And that knowledge is very valuable,” Alley said.

Alley likens the need to take action to the ways we’ve reduced the risks of getting into car accidents. The likelihood of a car accident is low, but we take action to prevent them or prepare anyway. Drivers buy antilock brakes, airbags, and seatbelts, and governments pay traffic police to watch out for drunk drivers and traffic engineers to create safer spaces.

“We spend a huge amount of our transportation budget on things that we're not sure will happen,” Alley said. Climate change preparation and prevention needs to be addressed similarly.

Even if the least extreme outcome occurs, communities and regions will still suffer major economic impacts from the need to repair and restore the losses and damages.

“It's hard for the situation to be a lot better, and it's easy to be a lot worse,” Alley said. With enough warming, an ice sheet really could collapse rapidly—an abrupt climate change—and drive much more sea-level rise than most people are expecting. As with preventing car crashes, it is important to research, prevent, and prepare for climate change and the impacts of sea-level rise.

Of course, what has caused these climate change threats is equally critical to solving them. Alley notes that a long path of scientific inquiry led to the “rather remarkable” result that “the biggest control knob on earth's climate over time has been atmospheric levels of CO2.”

“More of the variability in earth's climate has been linked to changing CO2 than anything else for many different timescales,” Alley said. “We’ve grabbed the biggest control knob, and we're turning it really fast.”

The existence of this “control knob” means if we change our energy choices by moving away from fossil fuels that accelerate the release of CO2 toward clean energy, we can help turn the dial back.

Which leads to another story.

“When I was a kid, you had to stand next to a wall to phone somebody. And we had dug up very large pieces of Arizona, Chile, and Utah to get copper to attach every house in the United States to every other house in the United States so you could stand next to a wall and talk on a phone,” Alley explained. But with the emergence of cell phones, many places will never have to dig up their land for copper to attach phones to walls.

“We could think of a world where people jump over what we did on energy to something that’s better in the long-term,” he said.

Longtime colleagues, George Denton, Scott Travis, Wally Broecker and Richard Alley at the 2018 Comer Climate Conference. In 1989, as a young researcher, Alley joined renowned climate scientist Wally Broecker's project to extract ice core samples in Greenland.

Much of Alley’s work today continues to investigate what will happen to sea level as the glaciers melt. The 2007 IPCC climate report roughly said that if the climate warms a little, there will be a foot or two of sea level rise by 2100. But if it warms a lot, there will be maybe a three-foot sea-level rise, or possibly as much as six to nine feet.

Understanding the scope of the impact’s magnitude is where progress has been made. Alley believes his work on abrupt climate change and that of other climate scientists has helped the public learn that this change is a reality. Documentation, measurement, and prediction are critical for tracking what’s ahead.

“We’re learning it to give it to policymakers” and provide them the impetus to do something now “to take out insurance against possible disasters,” Alley said.